Hughes. Douglass. Tubman. Great Americans. Great Black Americans worthy of nationwide celebration. But only on a walk around Howard University will you see their names on residence halls and admin buildings along with countless other important African and African-American figures. A recent exploration of the place conjured the most innocent of questions: could more diverse building names across the U.S. lead to more diverse mindsets among American graduates?

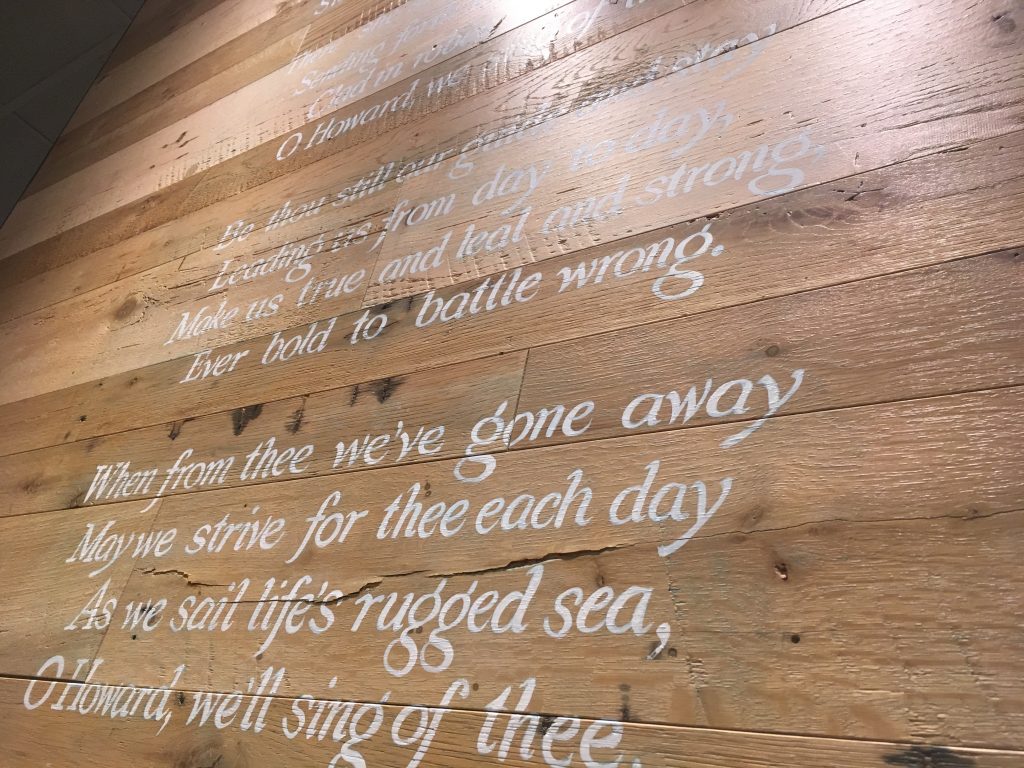

One of five Federally-chartered universities, Washington, D.C.’s Howard University is also one of over 100 historically Black institutions (HBCUs) in the U.S. and its territories. What started as a seminary to educate Black clergy has evolved to a leading comprehensive university with undergraduate, graduate and professional degrees, research programs and a hospital.

Despite the university’s progression as a world-class learning environment targeted toward African-Americans, in a mild irony it will always be associated with a time when freedom and opportunity was brutally limited for Blacks. Named for a white leader of the newly created Freedman’s Bureau for former slaves and chartered in 1867, Howard’s history is rooted in the post-Civil War struggle for Black equality and cultural and economic survival. The fact that, in many ways, this struggle continues into 2018 would likely shock and sadden Howard’s first students.

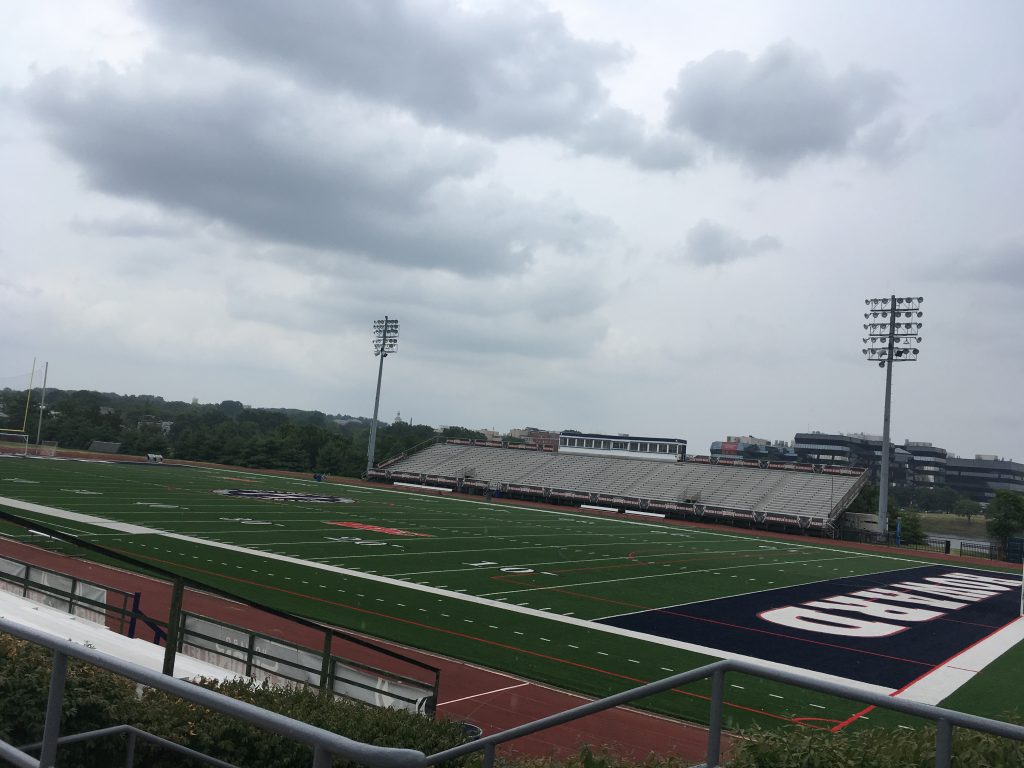

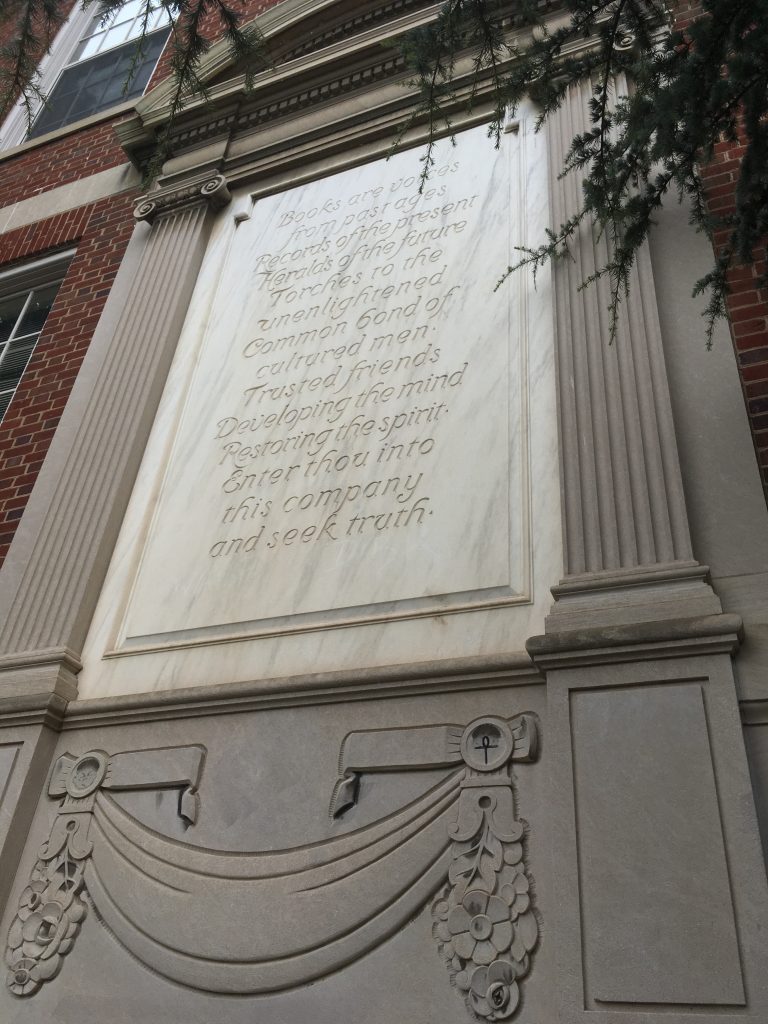

A beautiful and intimate campus that seems smaller than it is, Howard’s grounds are reminiscent of any other mid-Atlantic or Southern site from the mid-to-late 1800s, boasting plenty of Greek and Colonial revival and Federal architecture. Any visit to Duke, Johns Hopkins or Vanderbilt will yield similar examples of wide, symmetrical courtyards, grand stairwells leading to impressive red brick entrances with lots of spires, columns, clock and bell towers, wrought iron gates and engravings for good measure.

Some visitors seemed surprised by the grandeur of the place. The skeptic in me wonders at their implicit bias by thinking that being a historically Black school somehow rendered current building design trends obsolete. The generous stranger in me assumes their surprise was more in line with mine: how did all this acreage pop up in the middle of Georgia Avenue? Of course it’s Georgia Ave that grew up around Howard, but still it feels as though HU was laid down one stone at a time from heaven curiously into the middle of a metropolis swamp.

As I wandered the spaces between Georgia Ave and the McMillan Reservoir I kept subconsciously registering the placards affixed to each doorway, gate and construction sign. In a true V8 moment, it suddenly occurred to me after two hours that nearly every place was named for a Black American or African. Add to the prior notables the names of James Baldwin, Sojourner Truth, Colin Powell, Ralph Bunche and Ernest Just as names that grace many campus buildings.

To be clear, it wasn’t a surprise that an HBCU would honor the contributions of African-Americans in this way. My surprise came from realizing that I’ve never been on a campus that honored this many Blacks at one time, over time and in such a significant and visual way. Add to this the fact that not every one of these Black names is a household one. How many people know that Bunche was the first African-American recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize or that Just pioneered cell biology? Sad to say, this is radical shit.

This is so unique a phenomenon on other campuses that the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education has even published a list of buildings at American educational institutions named for Blacks, listing less than thirty such buildings at the top 25 campuses in the U.S., with only the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, UCLA and UC Berkeley having three or more.

Not every building at Howard is dedicated to an African-American, but as a first-time visitor that symbolic gesture immediately conveys to me who and what Howard honors, celebrates and memorializes. On other campuses, the names of American presidents, businessmen, inventors and academics demonstrate what they honor, celebrate and memorialize and in most cases, they aren’t a diverse lot.

What does it mean to pass only places named for wealthy, white men every single day? As the bi-racial alumna of an Ivy League University with only one building named for an African-American, I can tell you it means developing no attachment, no relation and no aspiration to those places or to those figures. In the most passive of ways, the structures of the campuses we live and work on become part of our daily experience and find their way into our individual and collective conscious.

Studies have shown that diversity inside the classroom improves all students’ cognition, problem-solving and critical thinking skills. So why wouldn’t diversity outside the classroom have a similar effect, with the added bonus of telegraphing to any visitor the priority that the campus places on racial and gender inclusion in memorializing structures. Beyond any one class, policy or short-term program, building naming is a literal putting of money and signage where administrative mouths are.

Given the newly erupted national conversation about the significance of historical monuments, now is a great time to consider the deceptively deep question of superficial building naming across America’s colleges and universities. Public diversity is not just about whether to destroy or relegate to museums Confederate statues but must also be about creating a more inclusive monument array, reflective of the contributions of all Americans.

I am dreaming of a future walk through Any Campus, USA. I see dozens of locations named for Black, female, LGBTQ and Natives along side Whites and men, whose names I don’t know, that I’m driven to Google and ultimately to learn about. I am dreaming of real diversity in the image that Any Campus, USA portrays to me and every other visitor as a believer in the accomplishments of all Americans and a promoter of their achievements, in stone.

Now that would be an education.