¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics: 1965 to Now

on view at Frist Art Museum through September 29

Housed in the shell of Nashville’s historic main United States Post Office, the Frist is a collection-less rotating exhibit museum that has breathed new purpose into a building destined for social and perhaps one day, actual, obsolescence. Today’s youth may have no concept of the United States Postal Service, but the USPS held an outsized role in my young life. Their red, white, and blue international express envelopes were the main vehicle of communication between me and my father, a military man who lived overseas. Those flexible cardboard sleeves were occasions not simply correspondence.

So, this museum holds a special meaning to me, not for its art but for its commerce. I grew up in Nashville but after more than twenty years away the city is all but unrecognizable. But this place, I know. I remember the art deco beauty and frenzy and majesty of its hollow bustle, now an energy that is regal and relaxed, as if it had always and with certainty been a museum.

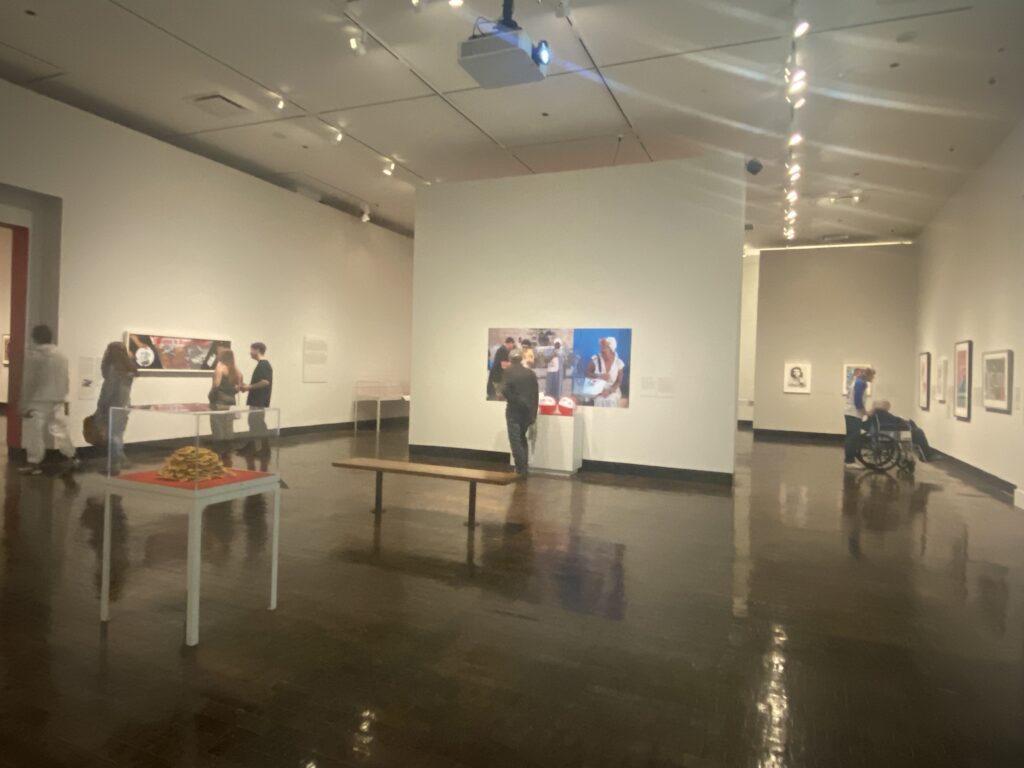

Frist’s on-view exhibit, ¡Printing the Revolution!: The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now (¡Printing!) is a bold endeavor that, while wholly different from the building’s art deco-industrial roots, succeeds in pacing with the grandeur of the landmark through both visual appeal and dramatic ideas.

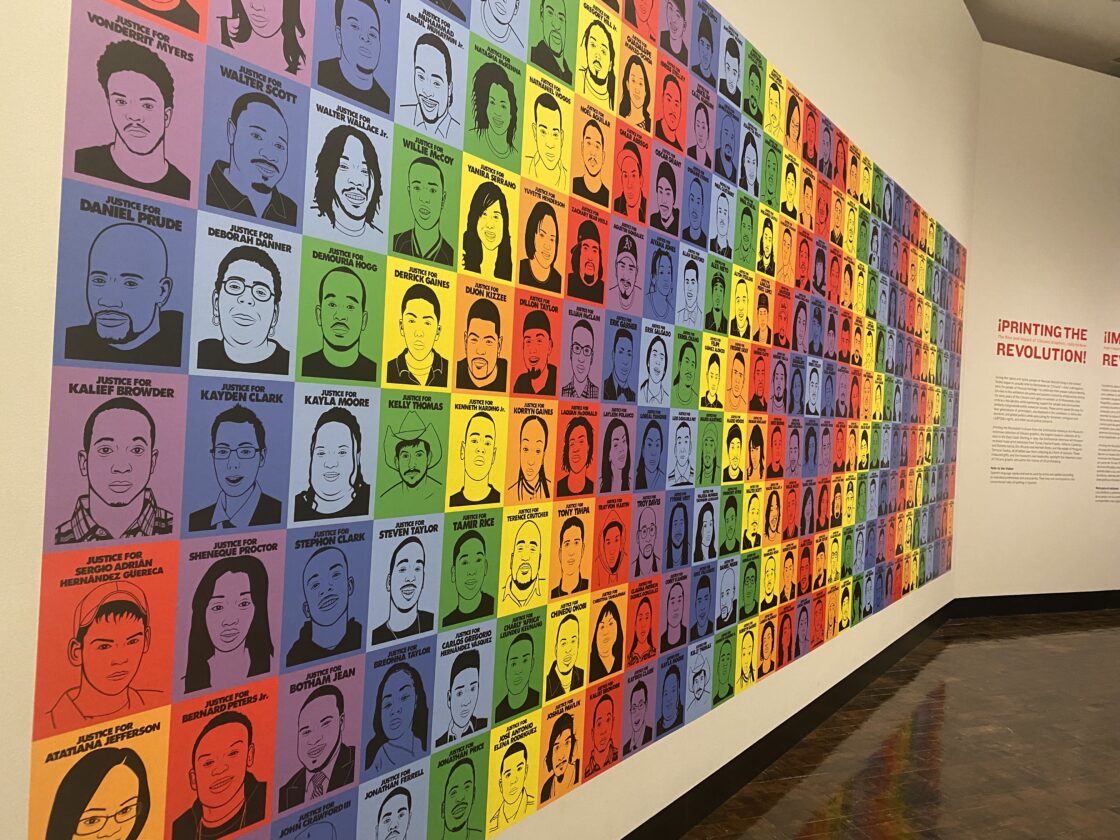

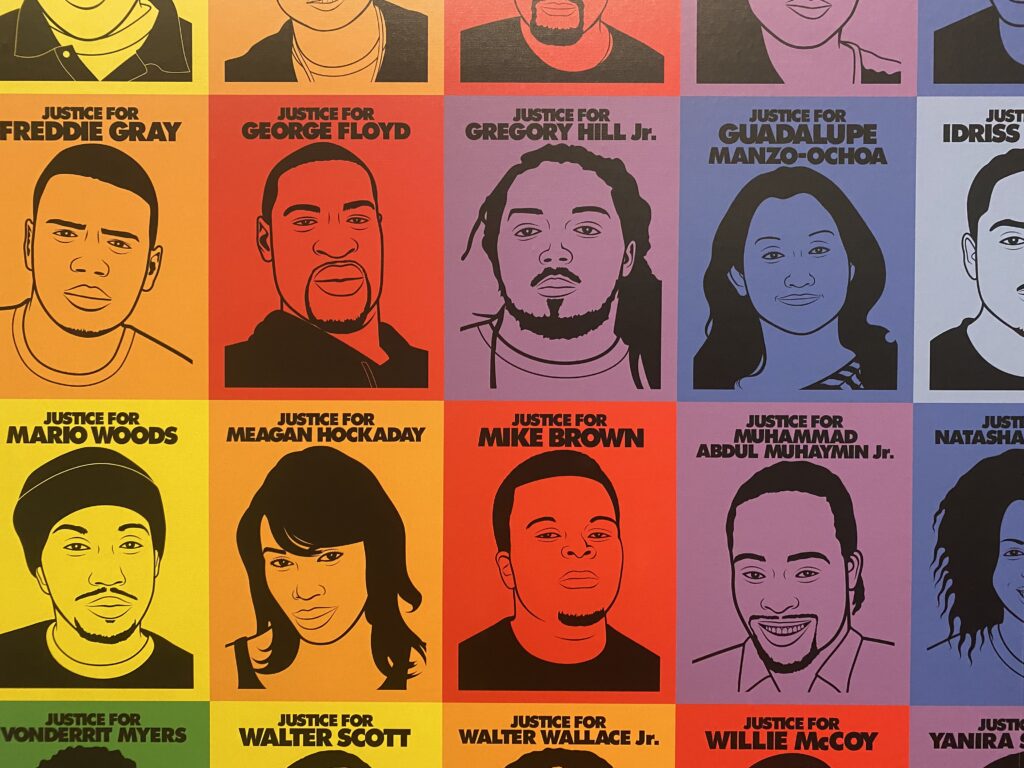

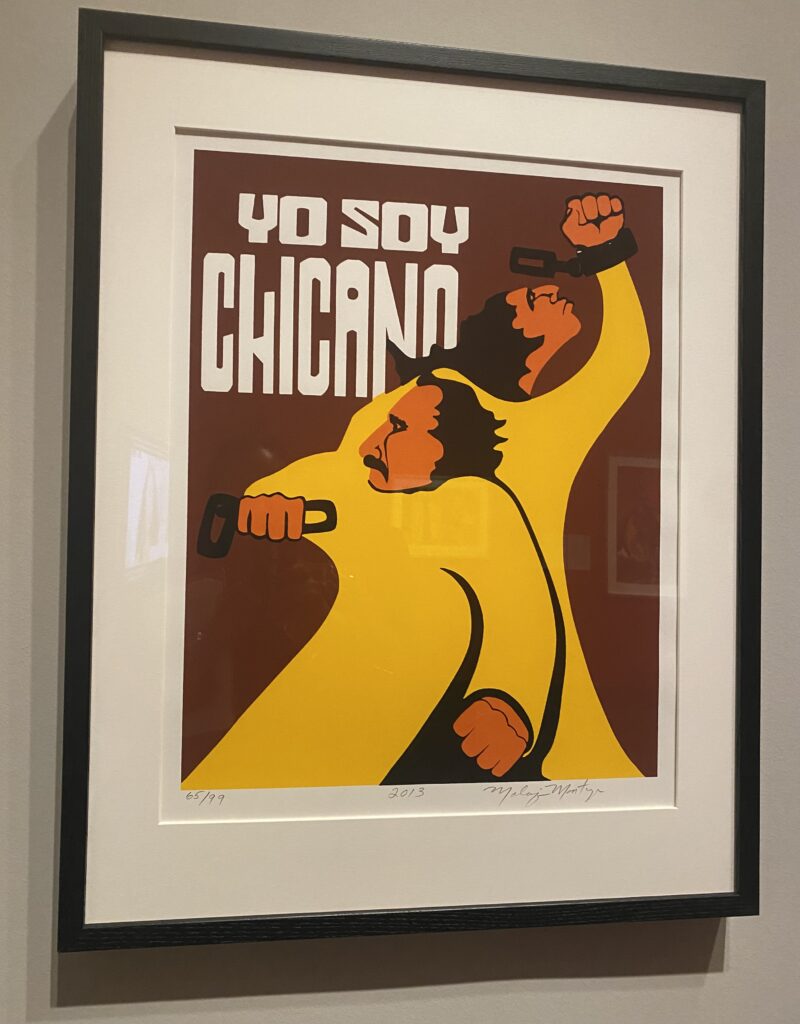

The tone of the experience is clear upon seeing the first work, Justice for Our Lives, 2014-2020, a massive, wall-cloaking piece by Oree Originol comprised of the beautiful faces of victims of police violence. Viewed on an angle the bright stamps create a diamond pattern of color and suggest that what’s to come will be vibrant and attractive, but urgent. And so, ¡Printing! is. Over the course of the exhibit, I learned about the meaning of the term Chicano, its derogatory beginnings, ardent reclamation and eventual community endearment. I learned about graphic printmaking as a scalable means of communication supporting the Mexican American civil rights activism of the 1960s and 1970s and which lives on today to distribute messages of resistance, records of lesser-told histories and calls to action.

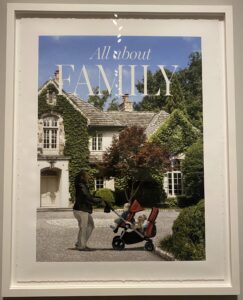

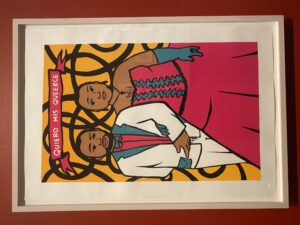

Apart from their historical significance, these graphical productions are also an artform that has informed contemporary artists in developing both new physical and digital forms and in expanding the dialogue into new realms of advocacy like Julio Salgado’s Quiero Mis Queerce, a Frida Kahlo-inspired quinceañera scene that retroactively celebrates the identity of his younger self who couldn’t do so in real life. Similarly reaching for new avenues of resistance, Jay Lynn Gomez centers migrant domestic service in the idealized lives of American families in her recent work All About Family.

As a museum nerd I took note of the many innovative techniques employed within the exhibit including allowing us to know the curators themselves. A unique video statement near the entrance opened the typically drawn curtain that often masks curatorial intent. This usual obscurity can sometimes contribute to a vague and omniscient arrogance that clings to many exhibits where we are not as viewers entitled to understand the perspective that formed the very show in which we are participating.

Assistant Curator Claudia Zapata explained how ‘open concept’ thinking contributed to the sense that the exhibit expands and evolves from past to present, from traditional print to digital with generations learning from each other and the ever-changing environment. This knowledge puts dynamic and essential context around the exhibit and fundamentally affected my absorption of it.

The use of digital went far beyond a touch screen or video playback, though those technologies were leveraged. ¡Printing! included hyper present tense digitally-mediated art like Zeke Peña’s augmented reality painting A Nomad in Love which animates a hummingbird and personifies a howling coyote when intercepted by a companion mobile app. The curators smartly paired the painting with a looping video of the AR experience creating an effortless way to experience the full impact.

A video captured the Times Square run of 1989 throwback Light Bright style Pesticides installation by pioneering digital artist Barbara Carrasco. In its time this would have been advanced and through today’s vintage-loving glasses I look with wonder at its simple ability to share stark news: migrant workers are being poisoned with pesticides and so are American families who eat farm produce. This provocative piece is just one of the dozens of nudges that remind us the problems identified in these arts are problems that have never been solved; problems that persist here and now.

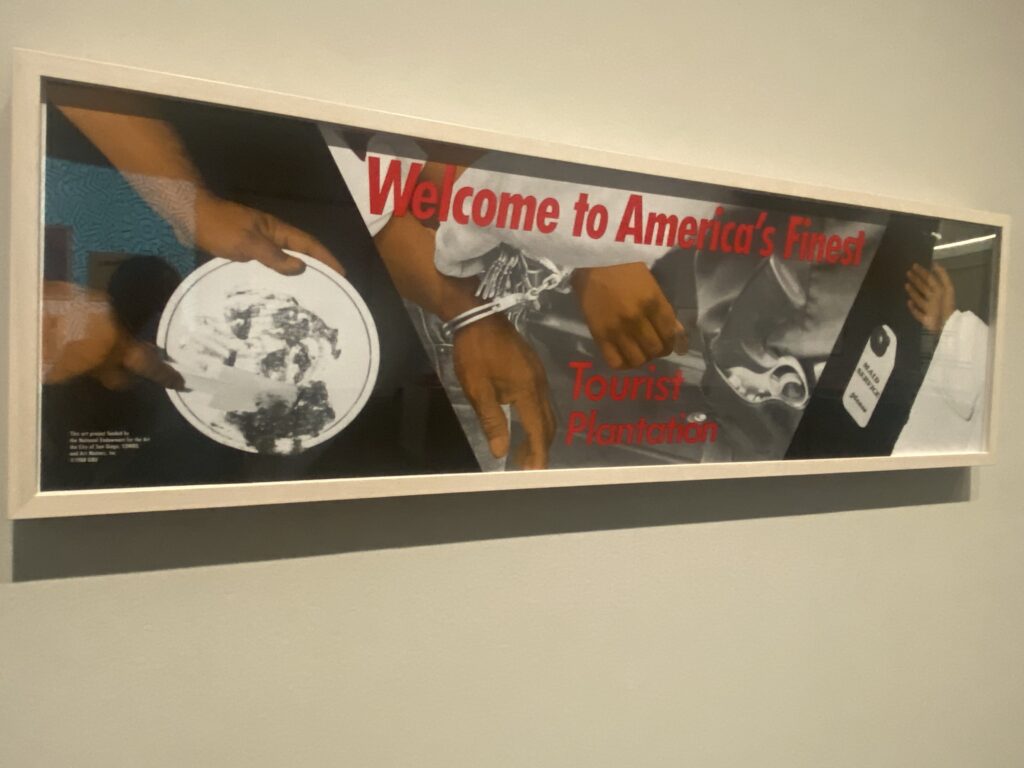

This exhibit is not overtly political in that there is no statement of belief or intention that the curators are asking us to agree with. It is the work, appropriately, that speaks to us. It is the work that provides an opinion and that calls us to consider how our migrant workers and immigrants are treated today and whether things have really changed much since 1960. The Jay Lynn Gomez piece along with Yolanda Lopez’s 1981 Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim? and the 1988 bus media signage Welcome to America’s Finest Tourist Plantation by Elizabeth Sisco, David Avalos and Louis Hock could all have been minted freshly today given how closely they track with current issues.

Pulled largely from the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection first formed in 1995 by a group of donor-collectors who believed in collecting as a form of activism, the exhibit also reminds us that high brow collecting isn’t only for the WASP set. This action helps to preserve and promote the goals and perspectives held by Chicano communities. With so much current discussion on the museum institution’s responsibility to the ‘public good’, this exhibit makes explicit the importance of including diverse sources of material culture in the definition of the public interest to ensure a complete historical narrative can be preserved and communicated.

Walking the floor, I heard people utter their immediate feedback with one woman exclaiming “I don’t think I get it”. We are taught, I think, that there is a right way to observe and receive art. She sounded almost worried or maybe defeated to realize that perhaps she couldn’t quite put herself into the same mindspace as the artist. I think it’s ok that she didn’t quite understand. We’re not meant to inhibit and reflect everything we see and museums perhaps must make sure they aren’t subtly telegraphing such expectations.

Maybe instead we should prize the visitor’s willingness to engage, their openness to accept what the artists thinks they are communicating even when they don’t know and offer them grace when their beliefs are challenged with allowance to wriggle and writhe in the uncertainty that art can conjure up. I don’t know, but I think the curators of ¡Printing! would agree. They developed an exhibition that offered so many doorways into the information that I can only imagine their ‘open concept’ provides a space for everyone to ‘get in where they fit it’. A refreshing feeling.