Something’s happening in Harlem. And whether you think it’s a good or bad happening is largely a matter of cultural orientation. I recently spent a wonderful evening celebrating Columbia University’s newest Harlem outpost for the arts, the Wallach Gallery. As inspiring as the socially conscious art was, it was also laced with irony. Is the latest fascination with Harlem another renaissance or a sign of its deterioration?

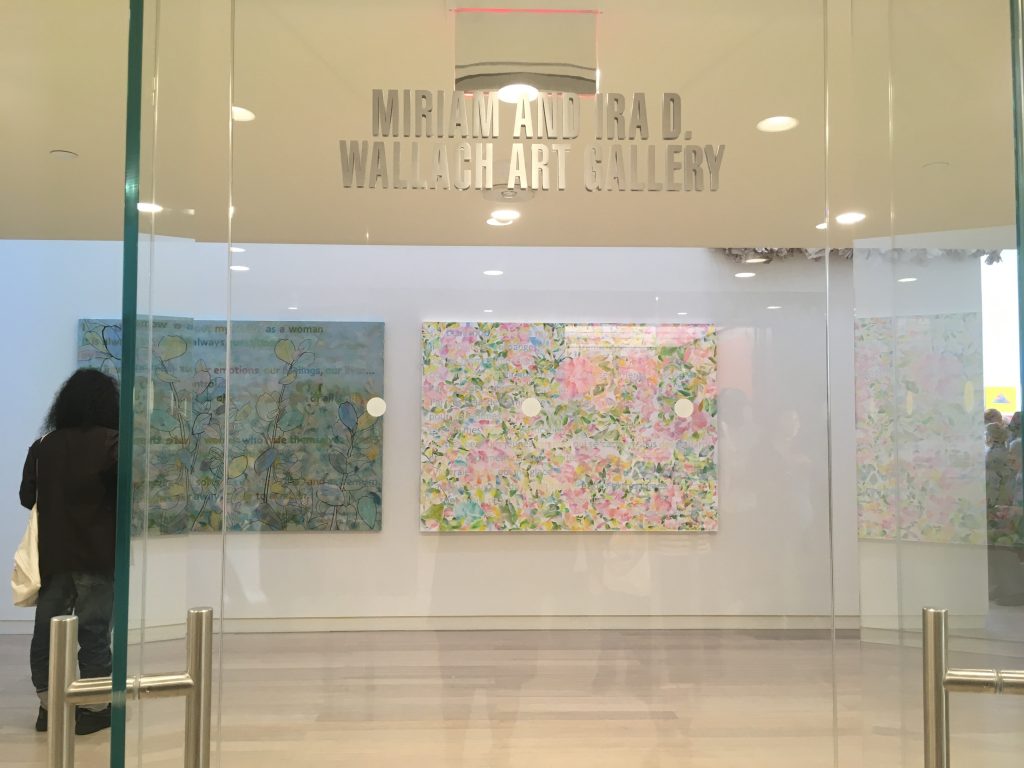

A beautiful Friday night should be spent in a beautiful place and the Wallach Art Gallery in the new Columbia University Lenfest Center for the Arts is a very beautiful place. Huge open spaces with floor-to-ceiling windows provide an impressive canvas for an art exhibit. And, a unique one. Museums and galleries so often seem dark and enclosed, but Wallach is literally awash in light with walls of windows sharing a breathtaking city view that almost serves as a piece of art itself.

The debut of the gallery’s “Uptown Triennial” signals the university’s entrance into what it calls “northern Manhattan’s vibrant art scene”. The initiative’s purpose is to showcase artists who live or work north of 99th street and so it has brought together many Black, African, Hispanic and other diverse talents into one intriguing space.

A long-time resident of the uptown neighborhood Morningside Heights, Columbia University seems to be jumping even farther onto the bandwagon of its own backyard’s increasing popularity. Beyond the Lenfest Center, the university also recently opened the Jerome L. Greene Science Center next door and is in progress of erecting new business school facilities around the corner.

The Ivy League school’s doubling down on “northern Manhattan” happens at a time when Harlem seems poised to become the next Brooklyn for hipsters, foodies and downtown ex-pats looking for bargain brownstones and authentic culture. Call it economic progress, call it diversification or call it gentrification; call it “about damn time” or “a damn shame”.

No matter which way you slice the answer to the question, the fact is Harlem is whitening, by the day. When you can walk down Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd or 125th street and pass as many white women with strollers as black men, you know the times are a-changin’. As I absorbed and enjoyed art from across the uptown diaspora, I just couldn’t shake the nag of irony. While the artists inside challenged social conventions and the erosion or manipulation of larger culture, their gallery space is, outside, part of this huge wave of gentrification in the country’s most famous and important Black neighborhood.

Once the home of Langston Hughes, Malcolm X and the Savoy, Harlem is now home to a Whole Foods and countless loft-style apartment buildings. Nothing says upper Middle Class utopia like Whole Foods. Don’t get me wrong: I think every human being should have access to healthy food and an overall granola experience. But here’s the challenge: with Whole Foods patrons come exorbitant rents. Hello granola, goodbye local residents.

Of course nothing is this starkly black and white, forgive the pun. But, it is an age-old cycle that has pretty much the same result no matter the town. Just look at Brooklyn. I lived in Prospect Heights in the early 2000s, when it was considered ‘in transition’. I moved there for cheap rent and many of my neighbors had lived there for a decade or more. Now it’s as expensive as Manhattan, if not more so, and has trendy restaurants and shops.

Again, I like nice things, so I have no problem with trendy shops. The problem I have is that back in Prospect Heights, those decade-comfortable residents have wound up moving out, and not by choice. This progress comes at a price for they can’t afford.

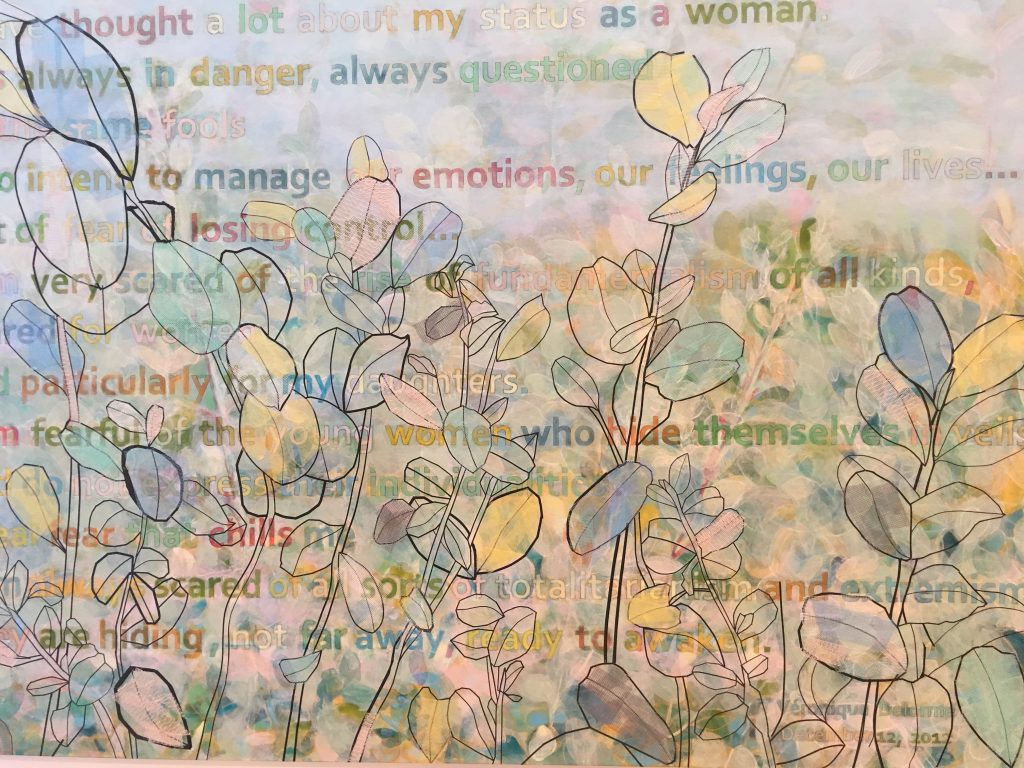

It’s this cycle and this history that gently pulls at my intellect and conscience while I take in the truly awesome “Uptown” exhibit at Wallach. There was so much to love and so much to consider in the many thought-provoking works. Many artists were pressing the status quo, like in Shani Peters’ fire-etched wood panel words and photographic mélanges of Black activism over the years.

Others opened up a world of culture by presenting a slice of theirs, like Bayeté Ross Smith’s 360 degree rap battle video or Miguel Luciano’s inventive bikes and shaved ice cart, which blasted the likes of Tupac and played a video loop of the cart in use handing out frozen goodies around town.

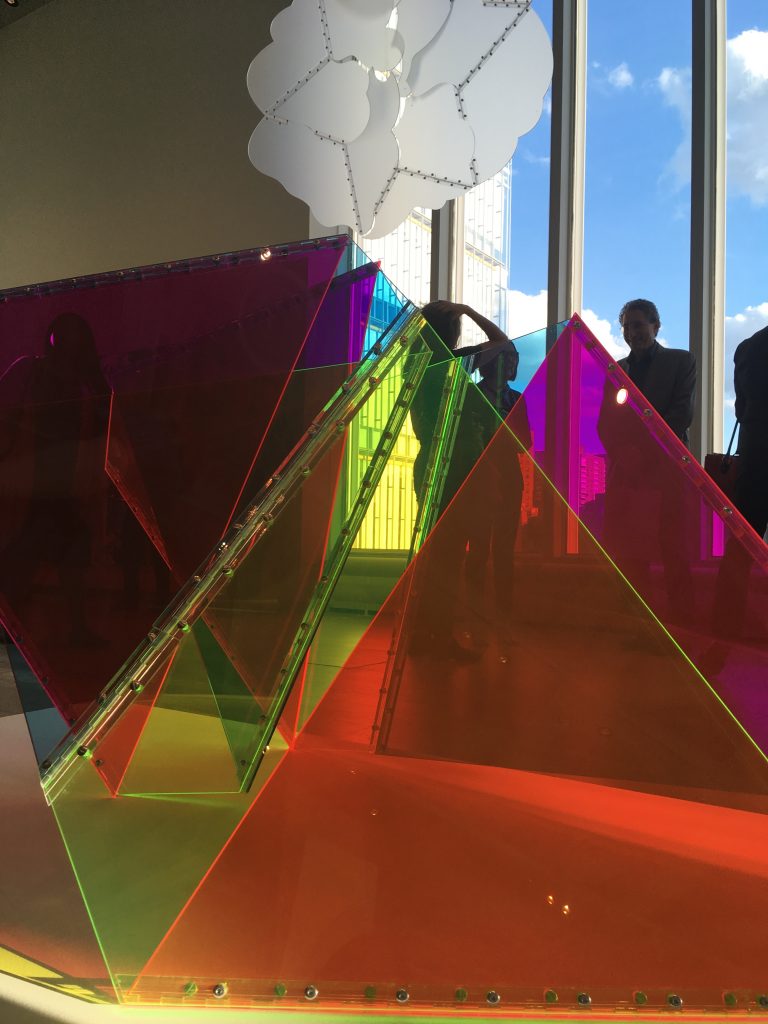

Still other artists seemed to be presenting beautiful works with implicit indictments of social norms, while still leaving we observers to interpret them as we saw fit. One favorite was Nari Ward’s neon and flower “Liquors” sign. Almost a gravesite for a typical liquor store fixture that is so common in poor and inner city neighborhoods. Less obvious but equally attractive were Marta Chilindron’s bright, geometric acrylics.

I’m no art critic, but “Uptown” was one of the most enjoyable exhibits I’ve been to in a long time. And my curiosity about the gallery’s place in the larger issue of community development hasn’t dimmed that enjoyment. I just wonder whether Columbia and other institutions have this same curiosity.

Harlem was once a haven for Black Americans who couldn’t live, work and play anywhere else. It was once a mecca for poets, artists and musicians who used their cultural reference as the basis for literature and art that is now part of the American fabric. It was once the home base for a generation of activists who refused to take a back seat in the most democratic nation in the world.

True, those historical figures entrenched in Harlem in part because they weren’t allowed to be anywhere else. So, I sometimes wonder whether celebrating the successes that grew out of segregation is a good thing. At the same time, the historical importance of the place is 100% tangled up with its historical reality. In a modern world where segregation is coming back with a gusto, fearing the white-washing of Harlem isn’t so much a question of excluding Whites, but of whether Blacks still have a place to be included. If not in Harlem, then where?

As I relished Columbia’s latest branch into Harlem and the hospitality of the Gallery’s opening night, I wondered whether the university sees itself as a contributor to the successful evolution of a future Harlem or as a player in the devolution of the old Harlem. One thing is for sure, you can’t stop progress, even when it comes with negative strings. I’d be happy just to know that Columbia wonders. That’s it’s own kind of small progress, even if the Harlem of history books is soon to be no more.