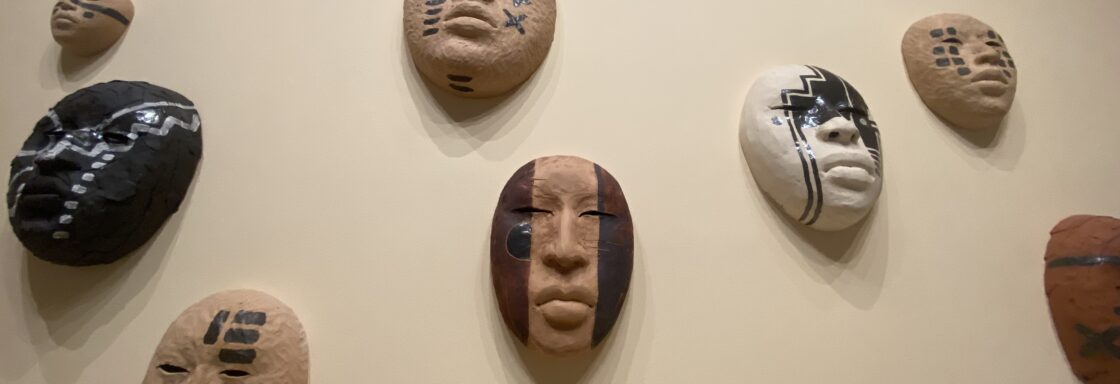

One afternoon at the Norton Museum of Art I had a conversation with a clay woman perched just on the edge of an oh-so-museum-looking white circular pedestal.

She was partly cream and partly reddish tan and her head was physically halved from crown to chin. She wrapped her own infinite hands around herself, magically preventing the violent tear from progressing below the neck. Toes spread, fingers curled, eyes fixed ahead, lips parted she looked right at me from her strange presentation cliff. She was persistent but trapped and numb to a place of sadness. But she also was protecting herself and so was she repairing herself which had a certain thread of inextinguishable hope. I felt like she looked at me; not to challenge me to see her, but to see myself, dividing, grasping on, firmly teetering but still there.

My tears were not sadness but relief. This clay woman saw me. She was Roxanne Swentzell’s 1986 clay ceramic named “Holding Myself Together”.

It’s maybe perfect that it was she that tethered me to Rose B. Simpson: Journeys in Clay and not a piece actually crafted by Rose herself. After all it was Rose who chose to transform this once individual survey into an experience in familial continuing. Roxanne, Rose’s mother, was featured in the exhibit along with grandmother Rina Swentzell and great-grandmother Rose Naranjo (affectionately called Gia). A pseudo conversation between the work of these three women of the Santa Clara Pueblo, one can imagine that to Rose, Roxanne and Gia they are just three of thousands sharing and shaping the tradition forwards and backwards through time. And maybe now I am a part.

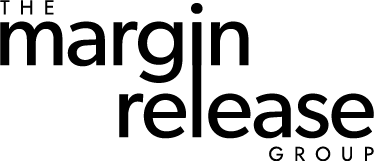

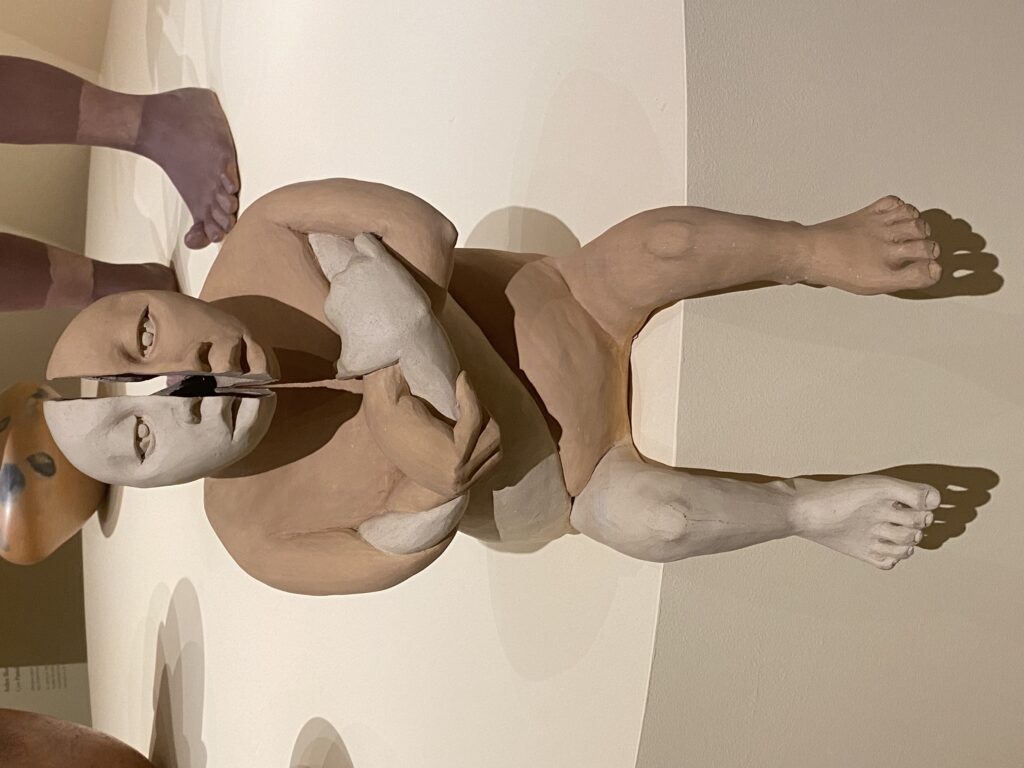

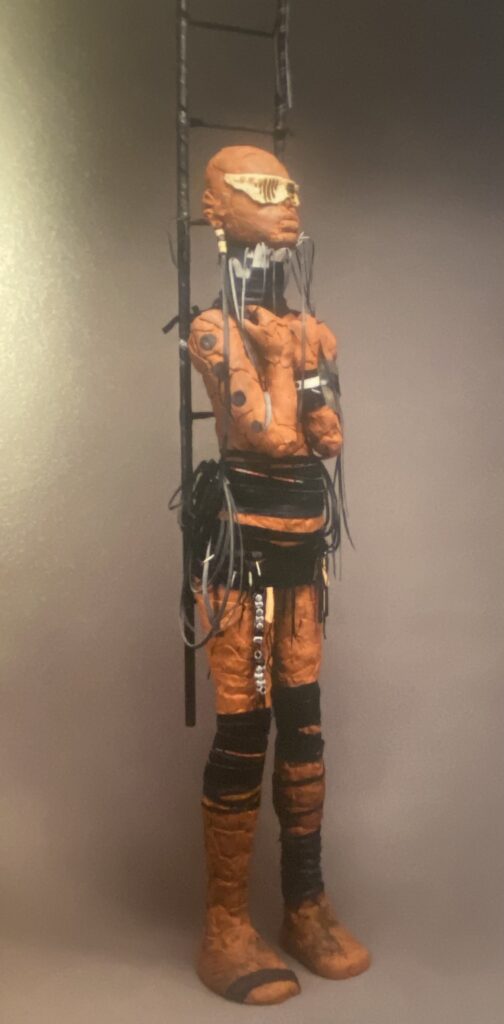

The majority of works provide a robust survey of Rose’s own creations, ranging from what curators Arden Sherman and Pamela Solares called “post-apocalyptic steampunk characters” to slim limbless figures enveloped in beads, ropes, small utilitarian and ceremonial clay and applied patterns. Some pieces directly reference the mother-and-child relationship while others are solitary and many are appended with scaffolding, extensions, adornments, enclosures and other elements that read as protective, celebratory and utilitarian.

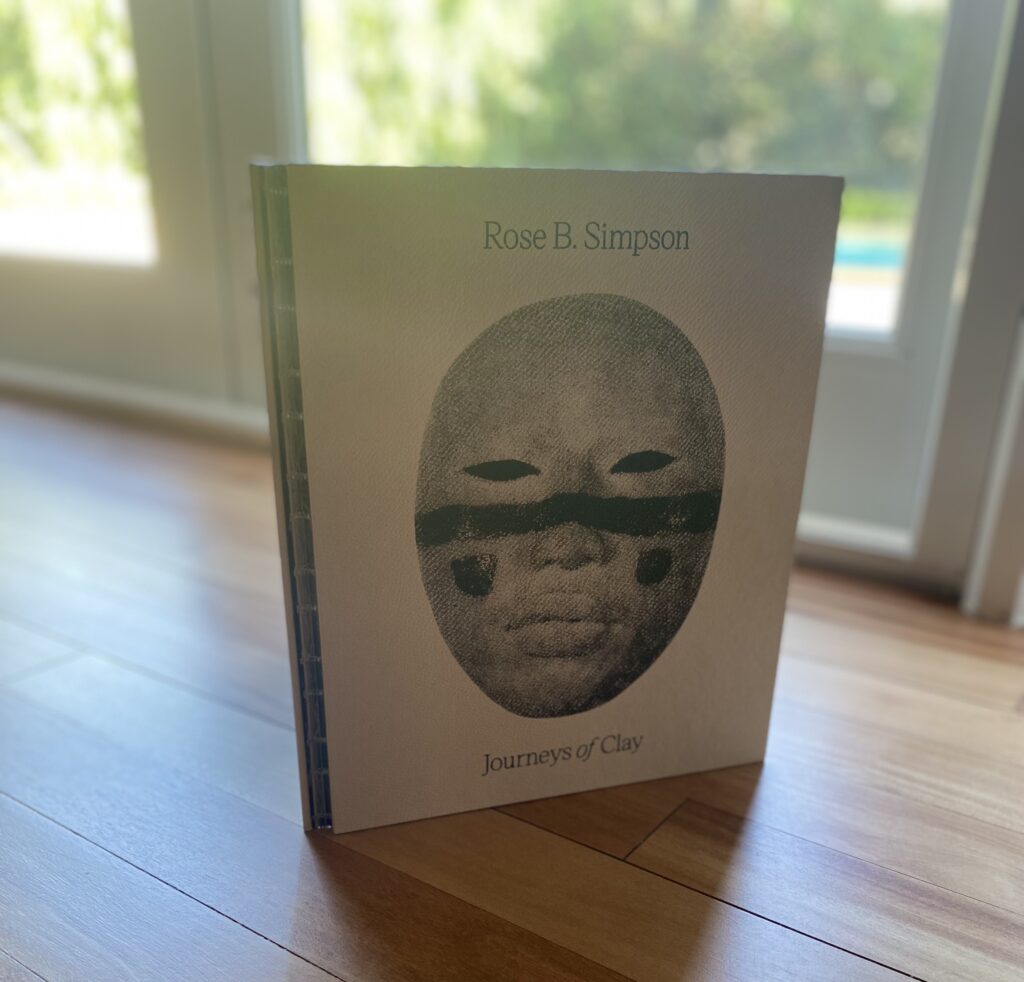

To better understand the true roots of their practice and how to interpret the exhibit, the exhibition book is a must-read. Produced by the Norton in concert with their exhibition series Recognition of Art by Women (RAW), the book is a combination of museum perspective on the artists and messages from the artists themselves. It is in the latter that the deeper meaning of the clay manifestations finally begins to break through the institutional wrapper of the exhibition.

On page 45 we hear Rose herself proclaiming that her sculptural work has a job and its job is doing and becoming its being. On page 46 we hear tell of the hundreds of ancestors that stand with and around her in and through her work. She welcomes us into her cyclical production of wondering and listening from which these pieces emerge. She quietly reminds us that her community’s language is Tewa and not so subtly confirms that English simply cannot translate the fullness of Tewa meanings.

What the print companion begins to allow that the exhibit did not attempt is revealing that their work is at least in part a response to the once and ongoing impact of colonial violence on Indigenous communities like theirs. Rose’s artist statement on her own website reads:

“My life-work is a seeking out of tools to use to heal the damages I have experienced as a human being of our postmodern and postcolonial era— objectification, stereotyping, and the disempowering detachment of our creative selves through the ease of modern technology. These tools are sculptural pieces of art that function in the psychological, emotional, social, cultural, spiritual, intellectual and physical realms. The intention of these tools is to cure, therefore, my hope is that they become hard-working utilitarian concepts.” – Rose B. Simpson

I don’t imagine this work is simply, only or even primarily art, but a form of technology in its most functional sense – tools to intervene in how we all might heal from the persistent violence of an unrepentant colonial past. Where curators see “post-apocalyptic steampunk” in 2018’s Great Lengths I see a post-colonial warrioress equipped with the Macguyver kit required to survive in this world that has done it’s damnedest to destroy her. Where the curators idealize maternal ancestral strength and artistry I see a female-powered cross-generational neural network of essential resilience that uses tradition, boundaries, teachings and lineage as scaffolding required to hold on to a life. I think these women see aesthetic as a trojan horse into meaning, into culture, a parachute in the cover of art and object to jet-pack their ways of thought and healing intent square into the heart of the most colonial of institutions: the museum.

In fact, Rose, Roxanne and their interviewer the activist, seed-saver and doula Beata Tsosie-Pena directly admit this in their comments between pages 87-99:

Beata: “I wonder about managing those contradictions that exist in being Indigenous but also being colonized. In the art world, museums and galleries – spaces that don’t have a function other than a space for viewing – remove the sensory experience of touch.”

Rose: “I feel a similar heartbreak when I’m around museums and collections that have grown silent and cold.” “[M]y works go out into the world and have conversations with people who may not understand what we’re talking about. So, they have to go into those white boxes, and they have to stand there and be a contrast to that world, and hopefully the prayer I put into them wakes people up to a consciousness they forgot, or haven’t had access to before.”

And this process – putting work out into a transactional art world – is not easy for her. “I’m not saying poor me, but I may not be able to do it forever because it hurts and it’s hard,”

Where curators see “post-apocalyptic steampunk” in 2018’s Great Lengths I see a post-colonial warrioress equipped with the Macguyver kit required to survive in this world that has done it’s damnedest to destroy her. –

As much as I enjoy the Norton and as deeply as this exhibition touched me, I know in my heart that the Norton could have used their resources, intentions and creativity to more vigorously promote Simpson’s and her family’s work as direct healing practice in response to colonial violence. Doing this begins to acknowledge the specific accountability that American museums have in preserving and promoting colonial values and more. To put on an art show is no longer the definition of innovation.

This is not so much a criticism as a challenge filled with hope and faith in our country’s museums’ willingness to begin to more ardently tackle the museum’s own accountability. I would love to see the Norton be in the vanguard next time.

Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay was on view at the Norton Museum of art in West Palm Beach, FL from March 23 through September 1, 2024.

Sources:

- Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay exhibit https://www.norton.org/exhibitions/rose-b-simpson

- Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay Norton Museum of Art published by Pacific

- www.rosebsimpson.com

- “Celebrated ceramicists in “Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay” exhibition at Norton” West Palm Beach Magazine Sandra Schulman March 29, 2024

- https://www.wpbmagazine.com/celebrated-ceramicists-in-rose-b-simpson-journeys-of-clay-exhibition-at-norton/#:~:text=Rose%20Simpson%20says%20the%20multi,felt%20I%20needed%20more%20context